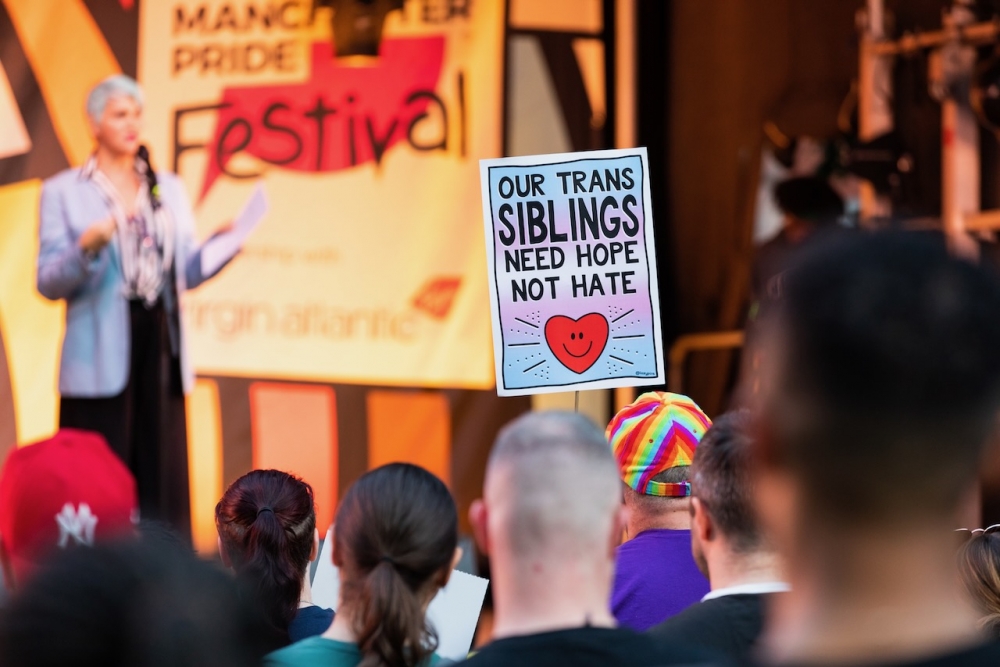

At Manchester Pride our vision is a world where LGBTQ+ people are free to live and love without prejudice. So then perhaps the most important question we need to ask is: how do we get there? If none of us are free until all of us are, then what do we each have to do to create a world where all of us are free?

As Manchester Pride’s Inclusivity Development Manager, it is my job to speak to a wide variety of professionals and community members about their LGBTQ+ inclusion initiatives, and then support them however I can to ensure that those endeavours genuinely contribute to intersectional and systemic queer liberation. In all my time doing this work, I have come upon the same barrier getting in the way of real and meaningful change time and time again: people are often informed of issues without properly understanding them.

What I frequently find happens is that people learn (usually through the news or social media) of a social issue or an inclusion tactic, but they do not learn the nuances of the full picture. For example, they might learn that we should put our pronouns in our email signatures as a way to be more trans inclusive, but they might not learn the role pronoun sharing can have in resisting cisnormativity and instituting opportunities for trans individuals. Without this deeper understanding, the work for trans liberation that is meant to follow the pronoun sharing doesn’t happen, those who aren’t yet trans allies may resent having to do something that hasn’t been given a reasonable justification (and indeed might take that resentment out on trans people), from here trans communities continue to be harmed by systemic oppression and hate and the organisation has done nothing more than tokenistic virtue signalling.

I’m not the only one to have encountered this problem. Black feminist leaders such as Angela Davis and Emma Dabiri have also spoken about this. And, continuously, a key trend seems to be that both the mass media and social media disseminate ‘information rather than knowledge,’ which Dabiri argues ‘tells you what to think rather than teaching you how to think.’ But when the media only gives you some of the information without the entire context, a consequence isn’t just that people fail to understand the issue, but they are also likely to inadvertently contribute to harming marginalised communities.

There are many different examples of how being informed without being knowledgeable can harm LGBTQ+ communities. Let’s look at three.

When we are only informed about the problem of queerbaiting, we might define it as an occurrence when someone implies that they are LGBTQ+ only to later reveal that they are cisgender and heterosexual. This is a problem because LGBTQ+ people, who supported the individual in question (maybe financially, maybe by platforming them and their career), will not only feel cheated and tricked, but it means that the diverse representation that is so desperately needed has (as usual) been denied and instead that voice and opportunity has gone to someone outside of our communities.

With this limited definition in mind, it is perhaps no surprise that Kit Connor, known for playing bisexual character Nick Nelson in Netflix’s Heartstopper, was recently accused of queerbaiting on social media after he was seen holding hands with the opposite sex. The online criticism (read: bullying) led the teen actor to quit twitter, only to later return feeling forced to come out as bisexual (read more here.)

So, did Kit Connor queerbait? In short: no.

Queerbaiting is a critical and media literacy term to describe a specific narrative structure in fictional stories. According to Judith Fathallah, queerbaiting involves ‘hints, jokes, gestures, and symbolism suggesting a queer relationship between two characters, and then emphatically denying and laughing off the possibility. Denial and mockery reinstate a heteronormative narrative.’ The function of queerbaiting isn’t just to deny queer representation, but to reinforce the systemic oppression of LGBTQ+ people by jeering at the very idea of their inclusion and insisting that heterosexuality is the only acceptable identity for the story’s characters (and, in turn, its audience). It is, specifically, a way to use fiction to harm LGBTQ+ people.

Thus, real people (like Kit Connor) cannot queerbait.

But they can be hurt by the accusation of queerbaiting.

In this instance, a young LGBTQ+ person experienced a great deal of online hate, resulting in a loss of their autonomy and privacy as an LGBTQ+ person, which in turn may have unseen consequences in their family and for their career. Furthermore, other bisexual people have now witnessed yet another example of bi erasure through this assumption that someone in an opposite-sex relationship must be heterosexual, further alienating them from their LGBTQ+ communities and causing many to feel less safe to authentically express themselves in both online and in-person LGBTQ+ spaces.

When the media represents or discusses HIV and AIDS, they tend to talk about the AIDS Crisis of the 1980s and ‘90s. While it is crucially important we remember this history, the consequence of continuously situating our understanding of HIV and AIDS in this period is that it means that for many people their understanding is over 40 years out of date. By being informed of the AIDS crisis without being knowledgeable of how the situation has developed over time, many people have outdated and harmful understandings of HIV, HIV+ people and, indeed, LGBTQ+ people on the whole.

An outdated understanding of HIV and AIDS causes a variety of harms:

In all of the above examples, people may be informed about the existence and historic harms of HIV, but their lack of knowledge about today’s context means that they not only contribute to stigma and hate against HIV+ and LGBTQ+ people, but they may even cause both institutional and physical harm to themselves and others.

It is a fact that austerity measures are hurting women the most. It is a fact that women’s services are needed now more than ever before. It is a fact that there are less queer women than men in positions of power, voice and leadership in our communities.

And it is a very pervasive myth that the inclusion of trans women will cause further harm in these areas.

In the UK, the legacy media has done a very efficient job of redirecting the fight for women’s liberation away from legislators and decision makers and instead against trans people, trans women especially. This has been done in 2 very simple steps:

In this context, it is no surprise that some women whose autonomy, needs and spaces are being erased from society are feeling particularly defensive at the moment, and are fighting like hell to protect themselves and their own. We should all be fighting like hell to protect, improve and ensure the unending continuation of women’s autonomy, needs and spaces.

We just shouldn’t be fighting trans people.

As I have explained in my article on trans inclusion, the fight for women’s liberation and trans liberation are both a fight against patriarchy. When we are informed of trans inclusion in women’s services and spaces, but we are not knowledgeable about trans identities and issues, then we are at risk of believing widespread misinformation and redirecting our energies against marginalised communities rather than those with the actual power to improve access to services and spaces for all women across the country. The result is vitriolic hate against trans people rather than holding politicians and the wealthy elite accountable.

We must remember who the enemy is. We must work together in a more organised effort for intersectional liberation. And in order to do so we must all have a strong understanding of trans identities and trans inclusion. To learn more, I suggest you read Manchester Pride’s Trans Resource.

As the above three examples demonstrate, both the legacy media and social media do a pretty good job of informing people about different social issues or inclusion initiatives, but a pretty terrible job at ensuring people are knowledgeable enough about these topics to actually support marginalised communities. Instead, they tend to cause hate and harm. And these are just three of many ways that being informed without being knowledgeable can be a serious barrier to effecting positive change. With the rise of anti-LGBTQ+ hate crimes, now more than ever do we need a concerted effort to improve the lives of our communities.

And so, if we are ever to achieve our goal in creating a world where LGBTQ+ people are free to live and love without prejudice, then we need to know how to resist this issue. Intersectional anti-oppression scholar Patricia Hill Collins offers two great suggestions. First, we must learn to ‘not believe everything one is told and taught,’ and second, we need to create ‘new knowledge.’ So the next time you come across some information about a social issue or a way to be inclusive, take a moment to research this area a little more carefully, and then spread that knowledge (not just the information) far and wide. One way to do this is to get involved in a campaign for social change, such as Manchester Pride’s I Choose Kindness campaign for tackling anti-LGBTQ+ hate crimes. For professionals and organisations that want support with their LGBTQ+ inclusion work, click here!

Together, let us use our collective knowledge to better organise our efforts and make this a world where all of us are free.